Sometimes, I’m delusional enough to think that he’s urging me on from the grave. My mission is to add to the heaps of writers and historians who have brought humanity to this man of mythic proportions. I especially felt this way on an isolated day over the summer in Weehawken, New Jersey. I visited the site where Hamilton was fatally shot in 1804.

Blustery Specters

You know, sometimes I’m caught standing outside on a particularly blustery day. The wind seems to move at a frantic pace, much like the strap-hangers in New York’s Penn Station who have meetings that they are late for and children who were expecting their father home an hour ago for supper. The wind pushes roughly around the atmosphere, and sometimes in its agitated pace slams against a solid surface like a brick wall… or a person.

When an overwrought gust of wind happens to hit my ear, I sometimes wonder if the disordered whooshing sound that it makes is actually the entangled voices of those from the past, specters gone long ago, but who still have much to say and sort out.

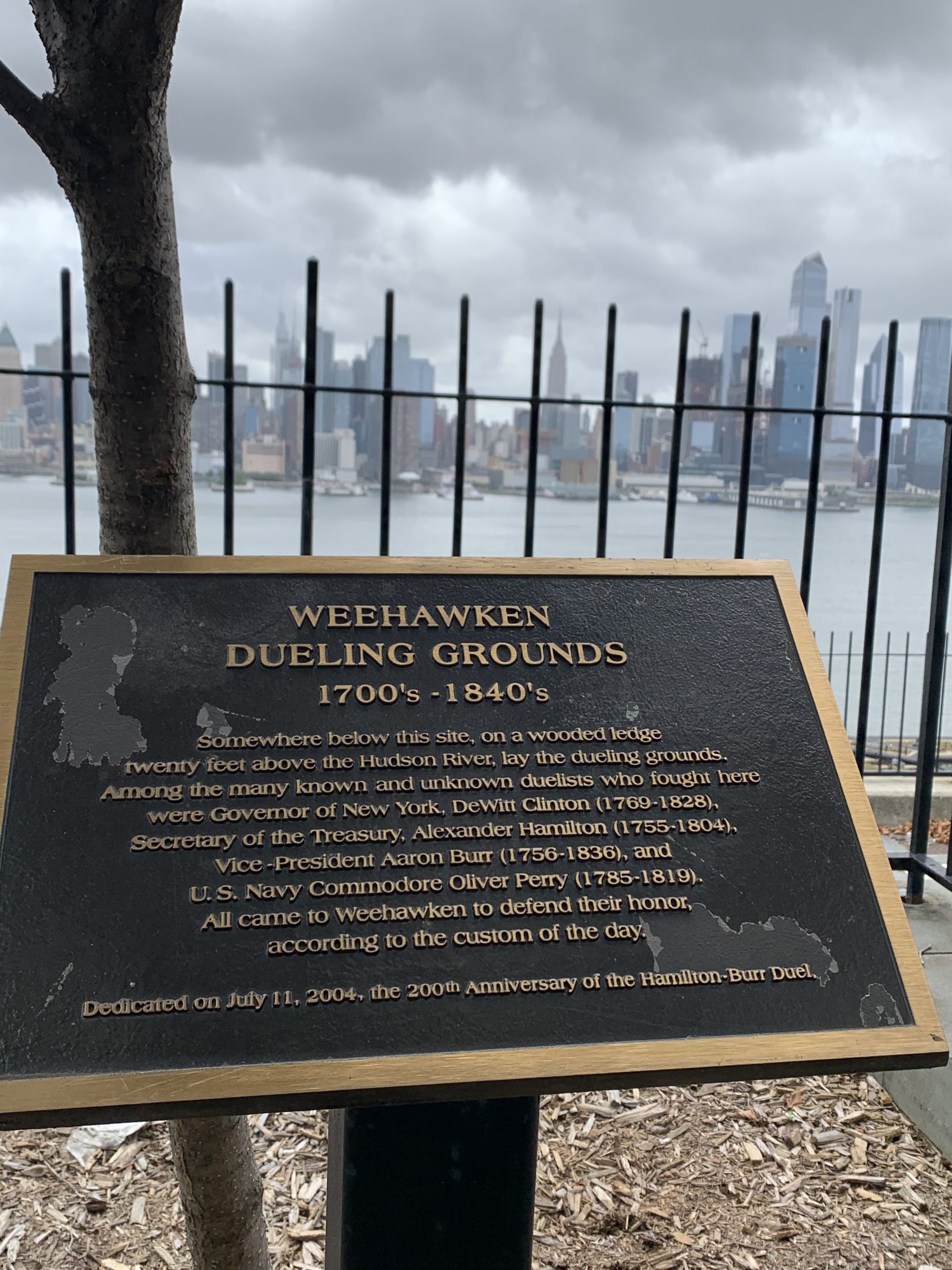

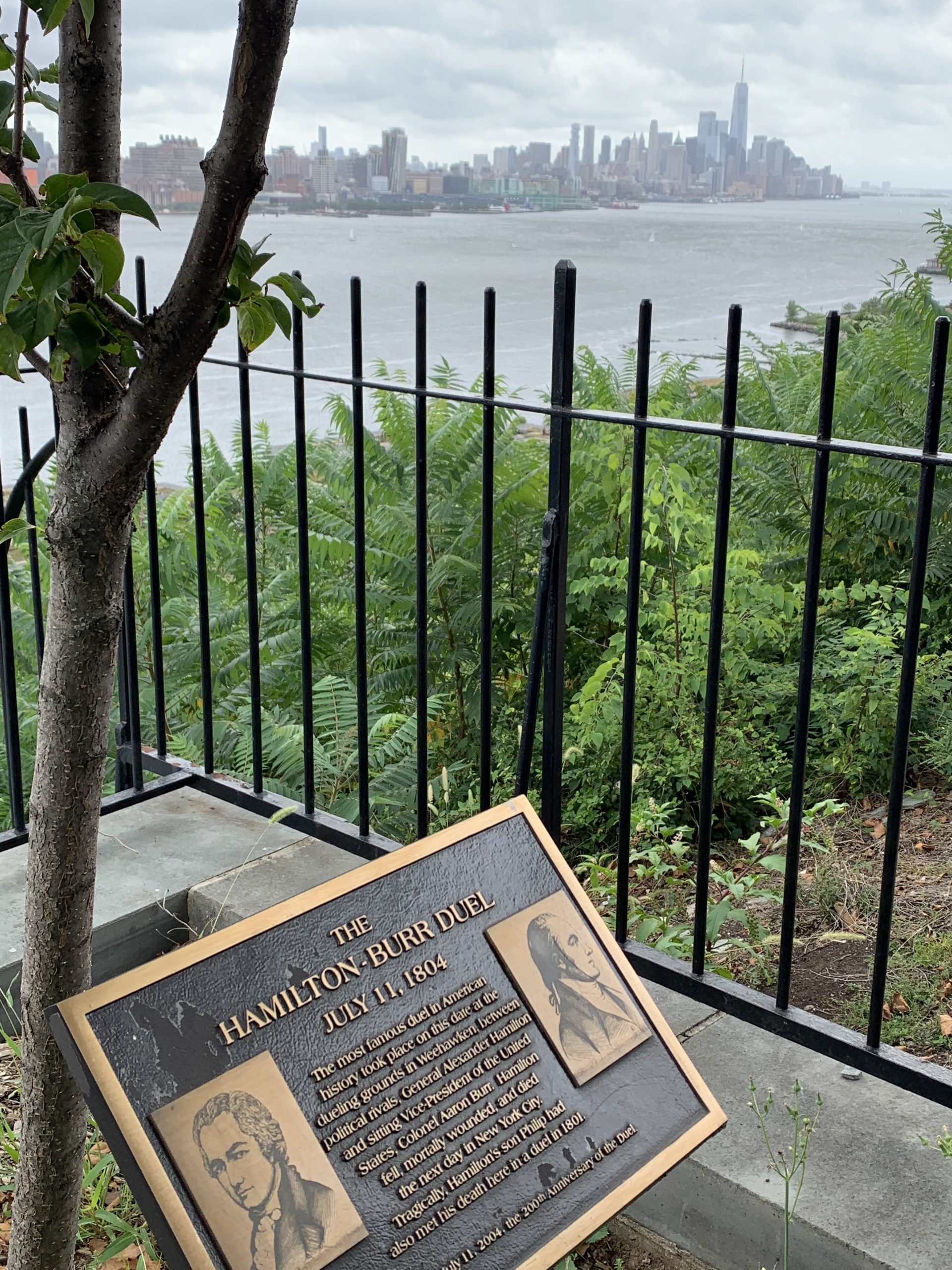

I ponder the likelihood of this idiosyncratic theory especially thoroughly at the Dueling Grounds of Weehawken, New Jersey. Here, I look out across the stretch of water at the skyline of Manhattan. It looks so close that I briefly fool myself into thinking that I could swim there. I look over the billowing minty green trees and copious buildings which precede the Hudson.

I’m slightly aware that to my immediate left, there are a half dozen or so small children all clad in Hamilton pajama bottoms singing a singular song from the hit musical, but I’m only half-listening to them. Mainly, I’m looking at the impressive city skyline. It’s a sight that always ignites awe from even the most jaded New Yorkers. As I stare out, a relentless rush of wind enters my ears and rattles my senses.

A Sign From Hamilton?

The rush of wind continues on down to my heart and grabs it in a most arresting manner, nearly knocking the breath out of me. In some way, from this burst of air, I understand that I am meant to put my phone down (that I’m clutching – waiting for the perfect shot), refrain from talking to my traveling companion, and simply imagine. Who am I to argue with disembodied force? And so, I do just that. I think deeply.

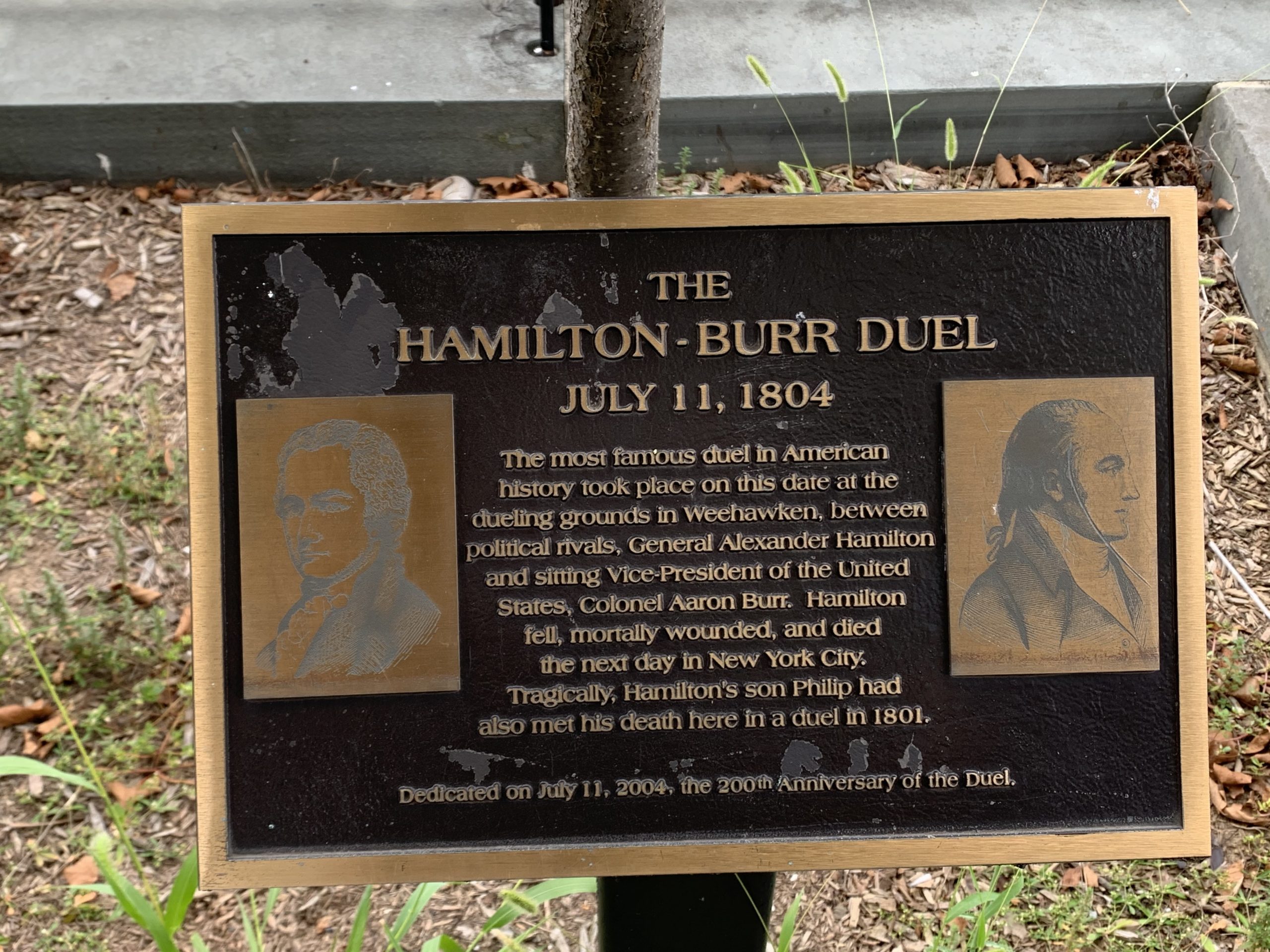

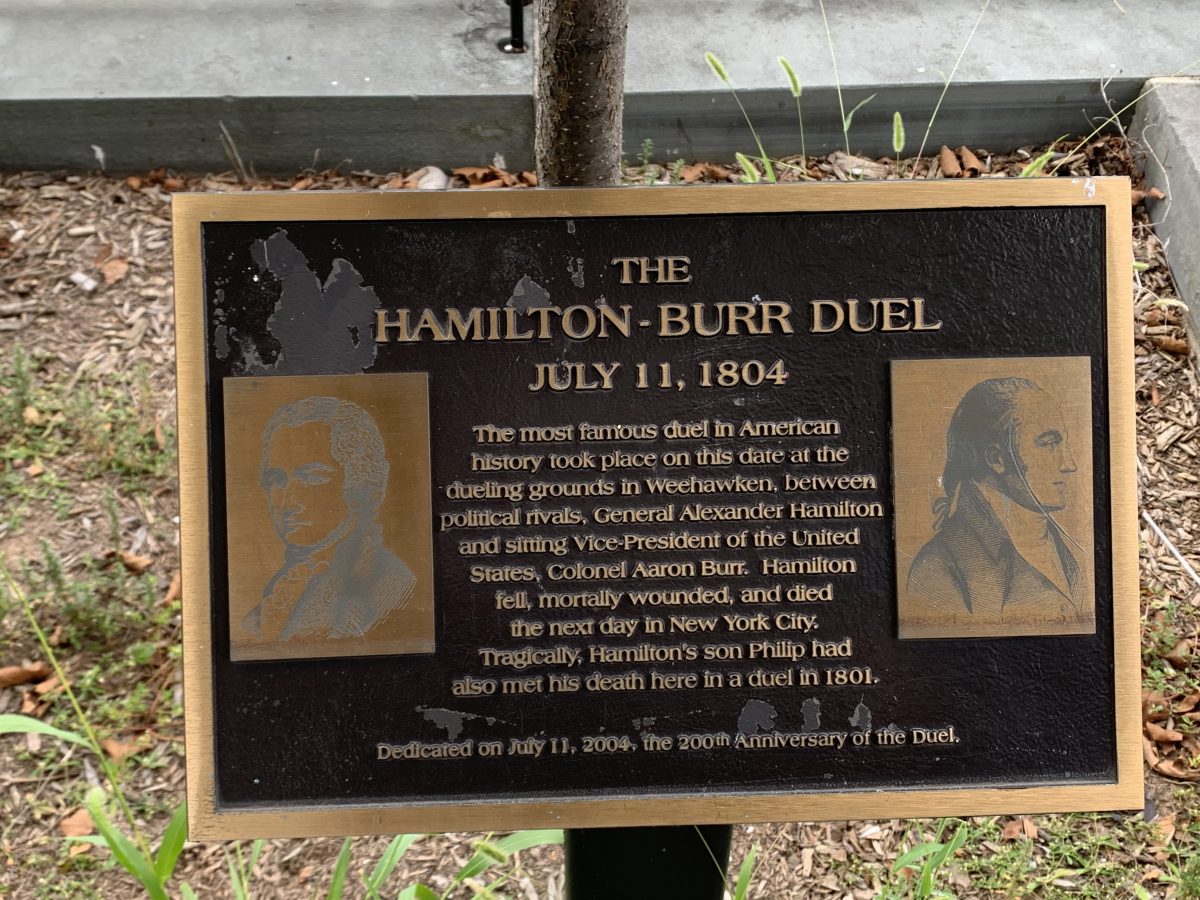

I try and create an image of this exact spot on July 12th in the year 1804. The year that Alexander Hamilton was killed in a duel by Aaron Burr.

Causes Worth Dying For

For most of us, it’s hard to imagine there being any cause or issued insult worth risking our life for in a shootout. However, the attribute of honor was unfathomably important to people in the 18th and 19th centuries. For many, defending one’s honor was worth dying for. Again, a notion most preposterous to just about all Americans today. (Besides, there’s a new American way of dealing with someone insulting your honor, it’s called suing, and we do it for just about any reason. If dueling in the 19th century happened with as much volume as suing happens in the US today…yikes.)

I’m fairly sure that even if I agreed to attend a duel to defend my honor, I’d wind end up pressing “snooze” on my alarm the day of the event in favor of staying warm and snug under my blanket. (Duels began right as the sun was rising in the sky.) I’m not sure that my honor is as important to me as the creature comforts of a weighted comforter and the calming scent of lavender pillow spray.

Possibly no one in the aforementioned time period regarded his personal honor as highly as our nation’s first Secretary of Treasury : Alexander Hamilton.

At just 12 years old, he wrote that nothing could possibly be as valuable as his honor and that he would be willing to die defending it. He would come very close to getting that chance more times than he might have possibly and previously imagined as a pre-pubescent boy. Even before the deadly match with Burr, Hamilton was involved in a number of duels (at least ten). Fortunately, all of them were settled before he actually had to draw his pistols.

Hamilton and Burr’s match was the boiling-point result of a detestable remark that Hamilton said (or more likely wrote) regarding Burr’s character. This exact series of words cannot be found in records of history. We only know that according to Aaron Burr, Hamilton’s words were considered to be insidious and inflammatory. Hamilton refused to apologize for his remark(s) and the reckoning between the men’s seconds was rendered useless. So, the two met in the early morning at the spot where I myself stood and visited this past summer.

Hamilton Monument

A black fence protects a very tall monument topped with a bust commemorating Hamilton. Also within the pen sits a boulder of a most peculiar rust color. The boulder was where Hamilton laid his head after he was shot. Eventually, his injury would kill him, 30 grueling hours later.

The area of Weehawken today is a very well-kept street on which a small number of gorgeous and historical homes rest. The residents of those homes have enviable views of New York’s twinkling skyline with the shining Hudson River between their drowsy, dreamy, abodes and the city that never sleeps.

I roughly shove my hands in my jean pockets and cast my eyes up to the gray sky full of clouds of a most depressing hue.

I begin to wonder about all of the thoughts that Hamilton, in his late 40’s, might have had as he faced an uncertain future while preparing for the shoot out. Did he have any inkling that he might actually die in his impending duel with Burr?

More than likely, he probably didn’t think that he would perish. But, he WAS willing to do just that if the duel came to it. He left a note for his family in the case that his life did end. He also left an unfairly heavy burden for them as well when he did perish. His eldest son, Philip, had been killed in a duel in Weehawken just a few years before.

Aftermath of Philip’s Death

Philip’s death was a constant source of grief for his wife, Eliza Hamilton. The passing of 19-year-old Philip incited lunacy in one of Eliza and Alexander’s daughters from which she never recovered. After his death, Hamilton left seven remaining children for his wife to raise alone.

In his mind, it was better to have a deceased father and spouse who perished with honor than to have a discredited and ruined living patriarch in their home. To lose one’s honor during this time period almost certainly spelled out the end of his political career and ambitions. To lose one’s honor literally meant to live humiliated as a public disgrace while bringing shame to his family.

However unsure Hamilton may have been about what fate awaited him on the dueling ground, he apparently was not uncertain about the future of his beloved city.

There are records that indicate that Alexander Hamilton was quite contemplative in his voyage from the shores of Manhattan to Weehawken on the morning of his death. Hamilton’s second in the duel, Nathaniel Pendleton, told the widowed Eliza after Hamilton’s death that her husband had looked at the fledgling Manhattan skyline as the two rowed to Weehawken and remarked, with an almost eerie foresight, “You know, it’s going to be a great city someday.“

St. Paul’s Chapel

One of the tallest buildings in the skyline during that time was St. Paul’s Chapel. It’s just down the street from where the founding father is buried at Trinity Church. He almost certainly would have had his eyes on it as he and Pendleton rowed away from New York. You can still visit St. Paul’s Chapel today (post-COVID). It’s nearly perfectly preserved from colonial/revolutionary days.

It’s a marvel that it survived the collapse of the Twin Towers. It housed many of the rescue volunteers during that time. Moreover, you can also still visit Hamilton’s grave down the street. It’s a pyramid-shaped structure that’s easily recognizable from the sidewalk which lays right next to it, with only the black-barred gate separating passersby from the monument.

I’m sure that Hamilton didn’t imagine as he looked at St. Paul’s Cathedral that his own burial service would be taking place not so far in the future and not so far from the Cathedral. As the sun rose in the sky on that day in 1804, Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr, Nathaniel Pendleton, William P Van Ness, and a physician stood and commenced with the gruesome task of witnessing or partaking in the defense of honor.

It is uncertain what exactly transpired at the duel, considering much of the evidence from the two seconds to Hamilton and Burr is a ‘duel’ itself.

Among historians, it is largely believed that Hamilton went first and fired into the air. The types of guns used for duels were not known for being very accurate. Whether Hamilton meant to ‘throw away his shot’ remains unknown. Next up was his opponent. Upon firing, Burr’s bullet lodged itself into Hamilton’s right abdomen. The bullet tore through several organs including his liver before becoming lodged in his spine.

Allegedly, Burr dropped to his knees and began crawling toward Hamilton proclaiming, “I must see him.” Evidently, there is a plausible chance that he did not mean to shoot Hamilton in the abdomen, or even to kill him. Again, the accuracy of these pistols was not remarkable, and any factor (a slight movement of the wrist, a sudden gust of wind) could carry the bullet in an unintended direction.

Pain and Adrenaline, a Legacy

As I meander the area in Weehawken, I cringe as I consider the pain of a piece of metal finding its way through one’s liver and nestling in one’s spine. I marvel at the bust of the man carved in stone standing before me. Also, I begin to ponder what he may have been thinking and feeling after he first fired his gun.

Did the rush of adrenaline prevent him from thinking or feeling much? Was he terrified that he had actually been shot? Or, as some scholars surmise, perhaps he was eager to throw away his shot and end of his life. Having lost his impromptu life coach (Washington) and his son (whose death he most likely felt guilty for, as Philip died protecting his father’s honor), he had in many ways stopped living years before his actual death. Maybe there was an eerie sense of calm that swept over him and enveloped him like the small waves in the Hudson as he knew that his life would soon be coming to an end.

History shows us that Hamilton worked relentlessly to know for sure what his future would look like.

I can relate to that. It seems as though nowadays I spend every moment behind my keyboard creating articles, penning a novel, writing blog posts, anything to secure my legacy as a “real writer”. It comes at the cost of losing friends, falling ill (mentally and physically), and shirking other responsibilities.

I too am relentless and do (naively to some) believe that my endeavors are purposeful and will yield fruit someday. However, as an outlier among my inner circle, I imagine Hamilton felt the same way. I know, after studying and researching this man, that I am hardly unique in the way that I think and obsess over leaving a piece of myself behind someday to be remembered in some significant way. From the afterlife, the man has brought me much solace and kinship. For that, I am eternally grateful.

Hamilton worked mercilessly to become somebody of great importance. He was certain of his own legacy as a great man. But how could Hamilton have known without a doubt that New York would become a great city? Possibly a lucky guess. Or, perhaps it was his damnable persistence, his inability to believe that anything that he touched and had a hand in shaping would not withstand the test of time.

Pursuit of Greatness

Alexander Hamilton and his exhausting pursuit of greatness strikes a chord in the collective emotional subconscious of literature lovers. I think this is because he reminds us very much of another (albeit fictional) American icon – Jay Gatsby. Gatsby is a man who Nick Carraway (the narrator of the novel) claims, “…was the single most hopeful person I have ever met and I’m likely ever to meet again.” Like Gatsby, Hamilton clung to his belief in destiny in which he is a ‘somebody’ with a heart-wrenching ferocity that is almost unbearable for the audience to follow. Americans like that. We like hopeful. We like the idea that persistence, grit, and hard work are the keys to success.

The founding father does not just strike a chord with literature lovers. His story is becoming more known by Americans from all walks of life. Mr. Hamilton embodies so much of what Americans hope, fear, and value. As Americans, we champion the individual and the individual’s strides, successes, tenacity, and ingenuity. So, we collectively uphold the stories of the singular hero who, against all odds, rises up and makes something of himself, and makes his country a better place as a result of his hard work.

Becoming Memorable

There is not a single American who doesn’t harbor a secret dream of standing out (in a good way) and becoming an individual of prestige and importance, a person whose legacy withstands hundreds of chapters in the book of time. It’s woven into the star-spangled fabric of our culture to champion the individual over the collective society.

Becoming one of the most memorable men in American history was Alexander Hamilton’s greatest goal. He wanted his name and achievements to be carried forth until the end of time. I don’t need to be the most memorable person in the future history of great American writers. But, I simply want be remembered long after I’m gone. Knowing that I’ll leave the world having produced writing that brings joy to thousands of people isn’t such a substandard goal for which to strive.

0 comment